Emergency airway management and ventilation procedures

General approach and assessment of the airway

Evaluate the effectiveness of the patient’s respiratory effort. Useful signs include respiratory rate, depth of respiration, accessory muscle use, the level of consciousness, skin color (cyanosis of the lips or ears is an indication of diminished oxygenation), upper airway sounds and lung sounds (auscultation of the lungs).

If the patient is able to talk clearly in full sentences this is reassuring about the function of the airway, because it suggests that the airway is not in immediate danger.

If effective respiration is absent you should act very quickly. Place the patient in the supine position, remove any visible foreign bodies from the oral cavity and open the airway with a head tilt-chin lift maneuver, or with a jaw thrust maneuver (the latter is used if there is suspicion of cervical spine injury because it does not involve movement of the cervical spine). In a patient who is not breathing check for the presence of circulation (pulse of the carotid or femoral artery). If the patient is not breathing, the assessment for the presence of pulse should last only for 5-10 seconds and not more, because resuscitation should begin promptly. If there is doubt, in a patient with no spontaneous respiration, it is better to assume that there is no pulse.

For the patient who is not breathing, start immediately giving mouth to mouth, mouth to mask, or bag-mask ventilation. The duration of each rescue breath delivered should be about one second. Watch the chest rise, to ensure that you achieve effective ventilation.

If there is also no pulse, or if there is doubt about its presence, follow the sequence of chest compressions and respirations, as described in the guidelines for basic life support. (2 rescue breaths every 30 chest compressions. Compressions should be provided at a rate of 100-120/min and compression depth should be about 5-6 cm, in the adult).

For better maintenance of a patent airway, consider placement of an oro- or naso-pharyngeal airway, a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) or endotracheal intubation, the latter being the most effective measure (choice depending on patient's condition, available equipment and expertise).

In summary, in an unconscious patient open the airway with a head tilt-chin lift maneuver, or if also cervical spine injury is suspected with a jaw thrust maneuver. If there are adequate spontaneous respiratory movements check oxygen saturation with a pulse oximeter. In case of cyanosis, or a low oxygen saturation administer oxygen by facemask to ensure oxygen saturation ≥ 95 %. If there are inadequate, or absent respiratory movements ventilate the patient with a bag-valve -mask device connected to an oxygen source. More details about these techniques are given below.

Maneuvers to open the airway of an unconsious patient

In case of a patient with impaired consciousness, the muscles relax. This often causes the tongue and tissues of the larynx to slide back into the pharynx and obstruct the airway. To prevent that, in case of an unconscious patient who is not breathing effectively, one of the two following maneuvers can be used:

The head-tilt, chin-lift maneuver

|

| Head tilt-chin lift maneuver to open the airway of an unconscious person |

The jaw-thrust maneuver

In addition to opening the airway with the head-tilt, chin-lift or the jaw-thrust maneuver, the airway must also be cleared of any secretions, blood, or vomitus. The most effective way is via a wide-bore, rigid-tip suction device.

|

| Jaw thrust maneuver |

Insertion of an oropharyngeal airway

This is commonly used in unconscious patients who are at risk for developing airway obstruction from the tongue or from relaxed upper airway muscle, especially if efforts to open the airway fail to maintain an unobstructed airway. It is a J-shaped device that can hold the tongue and the soft hypopharyngeal structures away from the posterior wall of the pharynx, thus keeping the airway open.It is only used in unconscious patients. An oropharyngeal airway should not be used in conscious or semiconscious patients because it can stimulate gagging and vomiting. Check whether the patient has an intact gag reflex. If so, do NOT insert an oropharyngeal airway. Clear the mouth of blood or secretions or foreign bodies. Select an airway of the correct size for the patient because if it is too small, it can press the tongue into the airway and if it is too large it can injure the throat.

Insertion of a nasopharyngeal airway

This airway adjunct is indicated when there is a need to protect the airway, but the insertion of an oropharyngeal airway is technically difficult or dangerous. Unlike the oropharyngeal airway, a nasopharyngeal airway may be used in semiconscious patients with an intact cough and gag reflex.(The gag reflex is a protective response that prevents foreign objects or noxious material from entering the pharynx, larynx, or trachea; it is not elicited during a normal swallow. It is evoked by touching the roof of the mouth, the back of the tongue, the area around the tonsils, the uvula, and the posterior pharyngeal wall. The response is a brisk and brief elevation of the soft palate and bilateral contraction of pharyngeal muscles. Occasionally, it can also lead to vomiting)

To select an airway of the correct size for the patient, place it at the side of his or her face. An airway of a suitable size extends from the tip of the nose to the earlobe. Use the largest diameter device that will fit. Lubricate the airway with a water-soluble lubricant or anesthetic jelly.

Insert the airway slowly, straight into the face (not towards the brain) without forcing the device. If it feels stuck, remove it and try the other nostril.

For Basic Life Support (BLS) see:

https://www.resus.org.uk/resuscitation-guidelines/adult-basic-life-support-and-automated-external-defibrillation/

For BLS and basic airway management, also see one of my videos (below). It clearly demonstrates many aspects of basic life support, such as head position to open the airway, how to deliver rescue breaths (mouth to mouth/ or how to use a mask, or bag with mask), the Heimlich maneuver to treat upper airway obstruction from a foreign body, the technique of chest compressions, basic defibrillation, etc. (to see it in full screen click on the symbol [] at the lower right corner).

Bag-valve-mask ventilation

It is indicated in patients who manifest inadequate oxygenation or ventilation, or respiratory arrest (absent respirations), usually as a bridge to intubation.Open the airway via jaw thrust or head tilt-chin lift maneuver (and if necessary also place an oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airway for better airway control). Then place the mask to cover mouth and nose with your thumb and index fingers on the mask and the remaining fingers wrapped around the mandible. This is the technique used by a single rescuer.

When there are two rescuers, use two-handed technique: Thumb and index fingers on either side of mask with the remaining fingers wrapped around the mandible.

Squeeze the bag and administer the air volume necessary to achieve chest rise. Give 1 ventilation to the patient in this manner every 5 seconds. Connect the oxygen tubing to the bag-mask

device and adjust the flow of oxygen to 15 L/min.

The adequacy of ventilation is assessed by observing the patient’s chest movement.

If you cannot ventilate the patient, add a naso- or oropharyngeal airway, reposition patient's head, and try again.

|

| Technique of holding the face-mask in bag-mask ventilation of a patient |

A video... I recommend these two videos, which show the technique of oro- and naso- pharyngeal airway placement and the technique of bag-mask ventilation. LINKS

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pqw_7K3Mz8M

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U4FrtssdyEQ

Laryngeal mask airway (LMA)

The LMA is indicated for patients in whom airway management is necessary, especially when the rescuer faces difficulties with bag-mask ventilation (not achieving adequate ventilation of the patient) but attempt for endotracheal intubation has been unsuccessful and ventilation is difficult. It is also indicated as an alternative method to endotracheal intubation if the health care provider is not trained in the technique of endotracheal intubation, or when tracheal intubation cannot be readily accomplished (some patients are difficult to intubate). It can also be used in many elective surgical procedures with relatively short periods of anesthesia.The LMA provides an excellent airway for the spontaneously breathing patient, and can also be used for controlled ventilation with an ambu bag.

An LMA is a tube fused to an elliptical mask (the cuff of the tube) at a 30-degree angle.The tube opens into the middle of the mask with three vertical slits. The mask looks like a small facemask and it has an inflatable rim that is filled with air from a syringe after insertion of the device into the patient's pharynx. After insertion the tube protrudes from the patient's mouth, and it is connected to a ventilation device.

Before insertion lubricate the posterior surface of the mask with

a water-soluble lubricant. Place a syringe in the cuff valve, and deflate the cuff (i. e. the mask) completely.

Open the mouth and lift the chin forward. Press the LMA against the hard palate, and slide it with the mask opening facing toward the patient's tongue along the posterior oropharynx, until it sits in position. This way you can minimize the risk of the epiglottis folding downwards as the LMA is advanced. The device is simply advanced until resistance is felt. It usually gets very easilly into position just by simply advancing it, until you feel the resistance and this is its major advantage. Then inflate the mask (or cuff) with the amount of air written on the device. The inflated mask provides a low-pressure seal around the laryngeal inlet but the LMA does not ensure an airtight seal to protect the lower airway from aspiration. This is a disadvantage in comparison to an endotracheal tube.

On the posterior aspect of the laryngeal mask tube there is a longitudinal black line. When placement of the LMA is correct the black line on the tube should be in the midline against the upper lip. Confirm proper placement also by evaluating for chest rise and the presence of bilateral breath sounds. After this has been confirmed, secure the device in place with self-adhesive tape round the tube. If spontaneous respiratory effort resumes, assisted ventilation should be synchronized with breathing to minimize the leakage of air from the larynx and the risk of gastric distension with consequent aspiration.

For the insertion of a laryngeal mask airway (LMA), I recommend this video

LINK: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-oXa-f5qkGY

Orotracheal intubation

Indications :Failure to maintain a patent airway (acute airway obstruction or imminent airway obstruction. [Two signs of upper airway obstruction are stridor and a muffled (hot-potato) voice.]

Need to protect the airway from aspiration (in patients without protective reflexes, i .e. unconsious patients with neurological problems)

Failure of oxygenation or ventilation (respiratory failure)

Respiratory arrest or cardiac arrest

Anticipated deterioration of the patient's respiratory function that will lead to respiratory failure

Establish intravenous access. Ensure that adequate ventilation and oxygenation of the patient are in progress and that suctioning equipment is immediately available in case of vomiting. Select an endotracheal tube: usually for men size 8 or 8.5 mm and for women size 7.5 or 8 mm. Inspect all components of the endotracheal tube for visible damage, inflate the cuff of the endotracheal tube to ascertain that the balloon does not leak, and then deflate it.

Select a laryngoscope blade: usually a curved blade size No 3 or 4, or a straight blade No 2 or 3. Connect the laryngoscope blade to the handle and check the light bulb for brightness.

Preoxygenation of the patient is performed by administering 100% oxygen via a mask for 4-5 minutes, without positive pressure ventilation using a tight seal of the mask, or by assisting ventilation with bag-valve-mask system (only if it is needed) to obtain oxygen saturation 90% or more. (Bag- mask ventilation is necessary in a patient with inadequate or absent respiratory movements).

Patients with respiratory arrest, agonal respirations (sporadic shallow ineffective respirations) or deep unresponsiveness need immediate endotracheal intubation without the administration of supplemental medications.

In the rest of the cases of emergency intubation, i. e. in patients not fully unconscious who have respiratory movements but need emergency intubation, for example because of acute respiratory failure, a procedure called "rapid sequence intubation" (RSI) is performed, which allows for rapid oral intubation without bag-valve-mask ventilation and requires the intravenous administration of an anesthesia induction and a neuromuscular blocking drug.

In summary, rapid sequence intubation (RSI) is used in situations where emergency endotracheal intubation is required (eg acute respiratory failure, coma) except from:

>Cardiac arrest (where RSI is not needed, bag mask ventilation and chest compressions are performed and intubation can be performed without the administration of an anesthetic and a neuromuscular blocking agent) and

>An anticipated difficult airway. Anticipated difficult intubation and difficult mask ventilation is a relative contraindication to RSI.

Factors indicative of possible difficulty with bag-mask ventilation: no teeth, obesity, facial hear, advanced age. (difficulty is expected if two of these characteristics are present).

Indications of possible difficulty with endotracheal intubation,

are the following: obesity, short neck, the chin being short, or longer than usual, a small oral opening, decreased neck mobility, a poor view of the posterior pharynx.In a case of anticipated difficulty, consider other methods of airway management, such as an alternative airway device (laryngeal mask airway), videolaryngoscopy (it improves visualization of the interior larynx), or cricothyrotomy.

Rapid sequence endotracheal intubation

Most patients requiring emergent intubation have not fasted and may have content in the stomach. In this setting bag-mask ventilation may inadvertently lead to gastric distention and increase the risk of aspiration. To avoid that, the patient is first pre-oxygenated with 100% supplemental oxygen via a mask (or a bag-mask connected to oxygen flow without actively compressing the bag). Then an induction agent and a rapidly-acting neuromuscular blocking agent are sequentially administered, as following:Administer a rapidly-acting anesthesia induction agent to induce loss of consciousness (such as Etomidate 0.3 mg/kg IV or Ketamine 1-2 mg/kg IV, or Midazolam 0.2–0.3mg/kg IV , or Propofol 0.5-1.5 mg/kg. -Propofol should be avoided in hypotensive patients)

and a neuromuscular blocking agent immediately after the induction agent (such as Succinylcholine 2 mg/kg IV, or Rocuronium 1-1.2 mg/kg IV). These drugs are administered as an intravenous push. The muscle blocking drug relaxes the vocal cords and this facilitates the passage of the tube between them.

In cases where cervical spine injury is suspected and not ruled out, intubation must be performed without movement of the head. In this case, the head and neck is maintained in a neutral position and immobilization of the head and neck is best provided by an assistant. When there is no suspicion of cervical injury, proper head positioning is very helpful: Then the patient’s head should be extended because this is helpful for the visualization of the interior of the larynx (the glottic opening, between the vocal cords). For better visualization, placing a small pillow or blanket under the patient’s occiput (under the back of the patient's head) aligns the pharyngeal and laryngeal axes. Exception: In patients with possible cervical spine injury head and neck should be maintained in the neutral position.

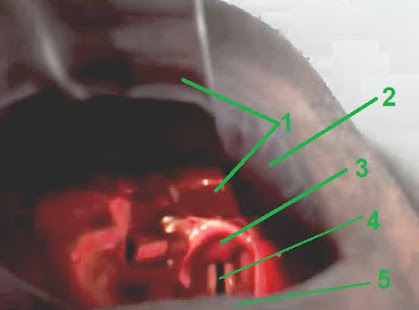

Grasp the laryngoscope firmly in your left hand and insert the laryngoscope blade into the right side of the mouth. Smoothly advance the laryngoscope blade inward, pushing with it the patient’s tongue to the left and up. The forearm, wrist, and hand are used as a single unit, without bending or flexing the wrist. The blade pushes the tongue as it is simultaneously moved to the midline, clearing a path for your gaze. When the blade has been inserted all the way, pull the laryngoscope handle up and forward exactly along its long axis which should be aimed toward a point above the patient's chin. This will raise the patient's tongue and jaw and allow viewing the epiglottis at the base of the tongue.

If using the curved (Macintosh) laryngoscope blade, advance its tip into the vallecula (the space between the epiglottis and the base of the tongue). If using a straight (Miller) laryngoscope blade, its tip should be advanced directly under and slightly beyond the epiglottis. (If neither the epiglottis nor the vocal cords are seen, the tip of the Miller blade is in the esophagus. Then locate the airway by lifting the laryngoscope along the direction of its handle while slowly withdrawing the laryngoscope blade.)

The laryngoscope handle should be at an angle of 45° to the patient’s body and it is pulled upward along the axis of the handle. This upward displacement of the epiglottis and the base of the tongue (by using any of these two types of laryngoscope blades) should uncover the vocal cords and bring them into view. Visual identification of the epiglottis and the vocal cords is a prerequisite for successful endotracheal intubation. External manipulation of the larynx with backward, upward, and rightward pressure (the BURP maneuver) on the thyroid and cricoid cartilage of the larynx, can be helpful to bring the vocal cords into view.

Insert with your right hand the endotracheal tube into the right side of the patient's mouth, while constantly viewing the vocal cords. Advance the endotracheal tube with its cuff completely collapsed, so that the tip of the tube reaches the vocal cords, without letting the body of the tube block your view of the vocal cords. Gently advance the tube through the vocal cords into the trachea until the cuff is about 2-3 cm past the vocal cords. You must see the tip and cuff of the endotracheal tube passing through the vocal cords to assure placement in the trachea. Usually, in the adult male, the 23 cm marker of the tube will be located at the corner of the mouth (21cm in the adult female), but this is an approximation since it depends on the patient's height. Once the tube has been inserted, the stylet should be removed (if you used one) and you should hold the tube with your right hand continuously in place until it is taped and secured and also inflate the cuff with an attached 10 ml syringe of air. Inflate the cuff of the tube with enough air to provide an adequate seal, so that there is no audible air leak with bag-tube ventilation, but do not overinflate it and then remove the syringe.

Check the correct placement of the endotracheal tube by applying bag-to-tube ventilation and observing chest excursions with ventilation and also via auscultation with a stethoscope of the chest (both lungs, also the lateral lung fields-the presence of bilateral breath sounds confirms correct intubation) and of the upper abdomen (no air movement should be heard over the stomach). A good way to confirm the position of the endotracheal tube in the airway, is to attach a carbon dioxide detector to the endotracheal tube between the adapter and the ventilating device .

Secure the endotracheal tube in the right corner of the patient's mouth with adhesive tape, to ensure it will remain in place. If the patient is moved, the correct position of the tube should be reassessed.

Initiate mechanical ventilation.

I recommend these two short videos showing the technique of endotracheal intubation LINK

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=10enx5T-2_8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lQZ8weWqRJY

GO BACK TO THE TABLE OF CONTENTS

LINK: Emergency medicine book-Table of contents

Levitan RM, et al: Airway management and direct laryngoscopy- A review and update. Crit Care Clin 2000;16:373 [PMID:10941579]

Goto T, Goto Y, Hagiwara Y, et al. Advancing emergency airway management practice and research. Acute Med Surg. 2019 ;6(4):336-351.

Stewart JC, Bhananker S, Ramaiah R. Rapid-sequence intubation and cricoid pressure. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci 2014 ;4:42-49. Available http://www.ijciis.org/text.asp?2014/4/1/42/128012

Bernhard M, Becker TK, Gries A, et al. The First Shot Is Often the Best Shot: First-Pass Intubation Success in Emergency Airway Management. Anesth Analg. 2015; 121:1389-1393Also see a couple of sites :

Life in the fast lane: http://lifeinthefastlane.com/ccc/rapid-sequence-intubation/

Critical care practitioner : http://www.jonathandownham.com/process-of-intubation-equipment-and-some-of-the-drugs-used/

The site is still under continuous development. Content is gradually expanding

No comments:

Post a Comment